For this blog post, I decided to read the short story “The Tenant” by Victor Lodato. This story is about an alcoholic named Marie who becomes a tenant of the McGregor family. She lives in a small house on their land where she mainly drinks and reads books. You learn that her parents died causing her to derail her fairly normal life as an artist, become an alcoholic (or maybe a more pronounced one), and live a fairly nomadic life with very few possessions. She befriends one of the McGregor kids, Harland, and ends up helping him become a stronger reader in return for manual labor and ultimately companionship. As time goes on, she sinks deeper and deeper into alcoholism and eventually is hospitalized. The story ends with Harland going through her stuff after her death and reflecting on how she helped him develop into the person he is today.

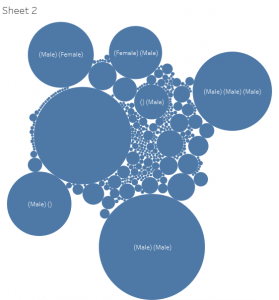

As I read the story, I noticed that “place” was an important part of the story. Therefore, I decided to create a network map with Google Fusion tables to illustrate the connections between important people and places in the story. The nodes are places such as Marie’s house and the hospital while the edges are the people that connect the places such as Marie and Harland.

This graph illustrates how places connect people in the story. For example, Marie’s House and the McGregor’s Land/House are important places which makes sense because that’s where the two main characters live and most of the character interactions take place. While this graph illustrates the importance between character interaction and place, it doesn’t innately show why these places are important to the story line. For example, the hospital only becomes an important place at the very end of the story when Marie gets sick and lots of characters come visit her. However, the way it’s represented in the graph makes it seem like it’s just as relevant throughout the story as the McGregor’s Land/house and Marie’s house. As a result, anyone looking at the graph would be missing important contextual information about why certain places have more connections than others.