Walter Freeman, the psychiatrist who popularized lobotomy, called photography his “magnificent obsession.” There’s no doubt that Freeman loved to shock, and his lobotomy photographs and films were part of Freeman’s arsenal of attention-getters.

But Freeman was also part of a long tradition of looking at a patient’s face and body in order to deduce the contents of her mind. So, in a way, he’s not as eccentric as his obsession might make him seem.

Johannes Caspar Lavater was an eighteenth-century German theologian who believed that people’s faces revealed the contents of their souls. He’s often credited with pioneering the practice of physiognomy: the idea that you can read people’s faces like books.

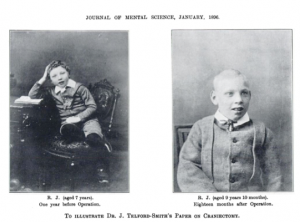

In the nineteenth century, Hugh Welch Diamond, the superintendent of the Surrey County Asylum, photographed his patients systematically. He believed that a physician could read a patient’s expression to discover her feelings. He also believed that confronting a patient with her own photograph could cure the patient by causing a shock of recognition.

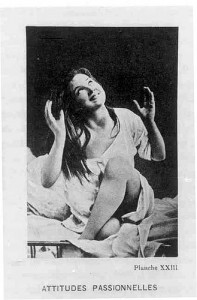

In the late nineteenth century, the physician Jean-Martin Charcot photographed his “hysterical” patients at the Salpêtrière, a Parisian lunatic asylum. Charcot believed that hysterics adopted characteristic poses, and that if he could catalog these poses, he could make sense of the disease.

Around the same time, police officers and anthropologists were developing a new way of looking at photographs: using them to classify criminals and to deduce the traits of “primitive” people. Freeman adopted many of the techniques that these photographers used: subjects are always pictured against a neutral background, in bright light, full in the face or in profile, with few of the softening gestures or props you might expect in a photograph of a family member or friend.

Freeman named Harvey Cushing as one of the inspirations for his devotion to photography. Cushing, an important American neurosurgeon, had all of his patients photographed before and after surgery. He also maintained a massive brain tumor registry. Cushing’s collection, held at Yale University, contains about 15,000 photographic negatives, along with about 800 anatomical specimens, taken from 1902 until Cushing retired in 1932.

When Freeman started taking patient photographs, the practice must not have seemed strange to him. Neurologists and psychiatrists had been using faces to deduce patients’ mental states since the eighteenth century. Photographs made sense as proof to Freeman because, like many psychiatrists before him, Freeman believed that people’s mental states were revealed on their faces.

If you’re curious about this subject, I’ve posted a bibliography of works related to photography in the history of psychiatry.

Thank you very much for so interesting posts. I have read them with interest, and will be a source of inspiration for my own blog dealing with photography and psychiatry: http://www.psiquifotos.blogspot.com Unfortunately only in Spanish, but the images do not need words and speak for themselves most of the times.

Be sure that I will visit again your site. Best wishes from Spain.

I just couldn’t go away your site prior to suggesting that

I really loved the usual information a person provide in your guests?

Is going to be again steadily to check out new posts

my homepage – ucsd email setup android