The short story “Eight Trains” portrays the narrator’s encounters with people during the daily commute by trains. The essence of the story is encapsulated in a sentence from the story: “It’s (human reality) all pre-planned”. All people the narrator encounters are the unchanged elements within her life, rather than something “simulat[ing] the chaos of life”, as the narrator describes. Therefore, the people who appear in the story revolve around the narrator rather than interact randomly between each other.

The network graph of the people’s connections in the story embodies the statement perfectly. As one can see in the graph, all nodes represented as the people the narrator encounters in the story are connected only to the narrator in the center.

The network graph of the people’s connections in the story embodies the statement perfectly. As one can see in the graph, all nodes represented as the people the narrator encounters in the story are connected only to the narrator in the center.

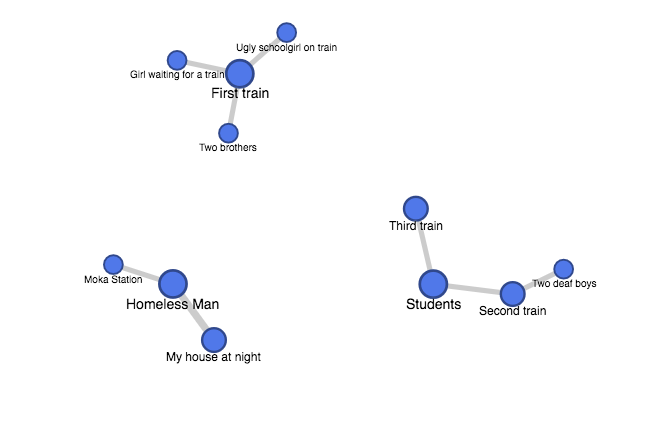

It is more interesting to draw the connections between the people and the places where the encounters take place. The nodes are then separated into three subsets. It is fascinating to notice that only the first half of the commute through eight trains are selected, possibly emphasizing the fact that the first half of the commute leaves a greater impression on the narrator. Also, the appearance of the “Homeless Man” as the central node corresponds to the significance of the character in the story, who appears both in the beginning and the end that marks the theme of the inflexibility of a repetitious life.

The network graph, however, does have its limit in that it cannot point out the significance of connections between the people and the narrator or between the people and the places. For example, one cannot tell what impacts certain characters have on the narrator’s life, or in what contexts certain characters appear in certain places. Such lack of dimensions prevents one who has not read the story from fully grasping the dynamics of the story.

As I browse through the map and play around

As I browse through the map and play around The Cartesian coordinate system, with time on the x-axis and the values of the two indexes on the y-axis, creates the framework of observing the fluctuations of the stock market throughout time. In this framework, investors can easily pinpoint the rising or the dropping points of the stock market and therefore induct the factors that caused the stock indexes to fluctuate. For the same reason, direction is used as the visual cue so that investors can easily see the boom or bust periods of the stock market from the slope of the plots. The context of the visualization can be easily clarified with the title “Stock Market Indexes from 1991 to 2011”.

The Cartesian coordinate system, with time on the x-axis and the values of the two indexes on the y-axis, creates the framework of observing the fluctuations of the stock market throughout time. In this framework, investors can easily pinpoint the rising or the dropping points of the stock market and therefore induct the factors that caused the stock indexes to fluctuate. For the same reason, direction is used as the visual cue so that investors can easily see the boom or bust periods of the stock market from the slope of the plots. The context of the visualization can be easily clarified with the title “Stock Market Indexes from 1991 to 2011”.

The interface of the website delivers an intuitive experience for the users. When one first enters the website, the home page introduces the early emergence of abstraction across different media, hinting at the idea conveyed later by the network graph that connections between artists of different fields lead to the development of abstraction. The button “Explore Connections” is placed in the lower right corner, a space arrangement that guides users to read the introductory texts in the middle first and thus equips users with the background knowledge to comprehend the significance of the network graph. The network graph is the heart of the website. The moment users leave the home page, they are taken to the page with the graph, with an “Overview” pane only automatically opened once that explains the logics behind the graph. The exploration of the network graph overall is a nonintrusive experience as buttons on the bottom navigation bar and on artists’ names on the network graph as nodes do not lead to separate webpages but the contents open side-by-side with the graph. Besides the UX design, the UI design also delivers an intuitive experience. The designers behind the project use Adobe Illustrator to construct the visual design of the contents. The color theme of “red”, “ivory” and “black” is used consistently throughout the design of the website and of the graph. “Red” marks only certain names within the artist catalogue and their corresponding nodes within the network graph to emphasize artists who have the most connections, or also the node of an artist that users click on, which then becomes the central node of his or her personal connections. The combination of UX and UI design therefore guides the users to understand the significance of the network structure behind the emergence of abstraction and how being in a network can foster creativity.

The interface of the website delivers an intuitive experience for the users. When one first enters the website, the home page introduces the early emergence of abstraction across different media, hinting at the idea conveyed later by the network graph that connections between artists of different fields lead to the development of abstraction. The button “Explore Connections” is placed in the lower right corner, a space arrangement that guides users to read the introductory texts in the middle first and thus equips users with the background knowledge to comprehend the significance of the network graph. The network graph is the heart of the website. The moment users leave the home page, they are taken to the page with the graph, with an “Overview” pane only automatically opened once that explains the logics behind the graph. The exploration of the network graph overall is a nonintrusive experience as buttons on the bottom navigation bar and on artists’ names on the network graph as nodes do not lead to separate webpages but the contents open side-by-side with the graph. Besides the UX design, the UI design also delivers an intuitive experience. The designers behind the project use Adobe Illustrator to construct the visual design of the contents. The color theme of “red”, “ivory” and “black” is used consistently throughout the design of the website and of the graph. “Red” marks only certain names within the artist catalogue and their corresponding nodes within the network graph to emphasize artists who have the most connections, or also the node of an artist that users click on, which then becomes the central node of his or her personal connections. The combination of UX and UI design therefore guides the users to understand the significance of the network structure behind the emergence of abstraction and how being in a network can foster creativity.